Hudson Fellowship Day 4

Friday, July 10, 2009 at 11:35PM

Friday, July 10, 2009 at 11:35PM

To see a nice quick overview of the work from previous years go to this page of past Fellows and mouse over each name to see an example of their work.

To see a nice quick overview of the work from previous years go to this page of past Fellows and mouse over each name to see an example of their work.For posts 2006-2010

please visit

sadievaleri.blogspot.com

Sadie’s current site is at

SadieValeriAtelier.com

UPDATE February 1, 2021

I have recently discovered that unfortunately this Squarespace blog has failed to maintain most the images for older posts on this blog. Luckily, the original Blogger version is still live at sadievaleri.blogspot.com and all the posts and images from 2006-2010 are still visible there.

For my current artwork, teaching, and blog please visit Sadie Valeri Atelier.

Friday, July 10, 2009 at 11:35PM

Friday, July 10, 2009 at 11:35PM

To see a nice quick overview of the work from previous years go to this page of past Fellows and mouse over each name to see an example of their work.

To see a nice quick overview of the work from previous years go to this page of past Fellows and mouse over each name to see an example of their work. Thursday, July 9, 2009 at 8:36PM

Thursday, July 9, 2009 at 8:36PM

Wednesday, July 8, 2009 at 6:18PM

Wednesday, July 8, 2009 at 6:18PM

Thursday, June 4, 2009 at 10:20PM

Thursday, June 4, 2009 at 10:20PM

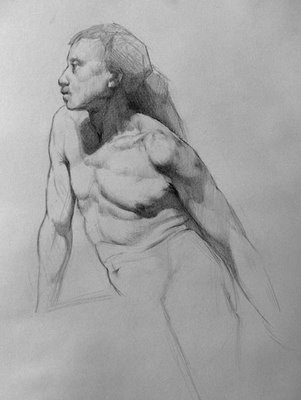

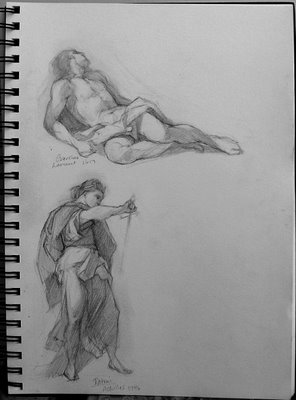

This is a recent study of a 3-hour pose. This was the last session of my Tuesday figure drawing with Michael Markowitz's 23rd St Studio. The next series of classes starts up while I am away for the month of July doing landscape painting in upstate New York but I'm hoping to resume in August.

Update on the "Big Still Life" a.k.a Bottle Collection:

I got a great tip for dealing with dust that has already dried into earlier layers of my painting, and spent some time today wet-sanding the surface. It was deeply satisfying to get all the grit and imperfections out of the painting and now I have a surface like glass!

UPDATE Jun 5: I made a new post here about the wet sanding process.

Saturday, April 25, 2009 at 12:14AM

Saturday, April 25, 2009 at 12:14AM  Winged Victory

Winged VictoryI started with a pencil line drawing on white paper and transferred the major lines once I felt confident with the drawing. It was difficult to control details and values on the textured laid paper and I found it worked best to sharpen white chalk pencil and hard/medium vine charcoal to a very fine point with sandpaper.

I'll be teaching this Sunday and then Monday I'll be out of town for 10 days, so the blog will be quiet a while till I get home and get my studio work going again. I've been chipping away at the big still life, hoping to post another finished detail soon!

Friday, April 10, 2009 at 1:04AM

Friday, April 10, 2009 at 1:04AM  Wednesday, March 18, 2009 at 9:38PM

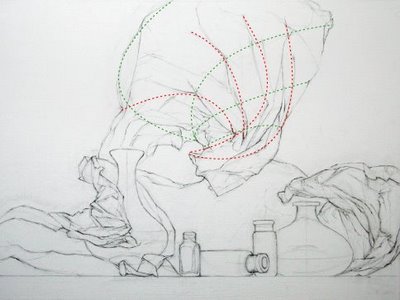

Wednesday, March 18, 2009 at 9:38PM  I thought it might be interesting to show how I am cross-referencing movement curves, or pathways. The red lines are the obvious ones, the finger-like folds fanning out from the spiral-crushed center. What is exciting is to find the secondary lines of movement, the green lines. Together they make a meshed network, and you can find them running nearly any direction.

I thought it might be interesting to show how I am cross-referencing movement curves, or pathways. The red lines are the obvious ones, the finger-like folds fanning out from the spiral-crushed center. What is exciting is to find the secondary lines of movement, the green lines. Together they make a meshed network, and you can find them running nearly any direction.

Wherever these curves intersect there is an "event", a significant landmark.

This approach really helps me plot and organize what at first seems like an overwhelming jumble. The network of pathways continues to subdivide in deeper and deeper complexity, so the deeper into the drawing, the easier everything starts to have a logical place. It always amazes me to see that even something "random" like crumpled paper has an internal logic.

One of the most important things I have learned about drawing is to not be afraid to change what I've put down before. I think it's common to draw a nice area and then realize it's in the wrong spot, and kind of "fudge" the drawing all around to keep the "good part".

What I have come to understand (and continue to try to understand) is that the overall logic is the most important thing, there is no "good part" of a drawing if the whole is not harmonious.

Thus I am ruthless with my eraser. Inevitably as I am drawing (and I think anyone who draws will relate!) I come to a point that doesn't "fit". I thought everything was right, but I get to a more detailed area and realize it's totally the wrong size and shape to fit all the detail that belongs there.

I've given up trying to preserve anything at all. If it's wrong, it's wrong, and I think in order to learn to be a truly accomplished draughtsperson we have to be willing to scrap all the previous work in order to improve the whole drawing. I did it many times for this drawing.

There must be a determination to really understand what is happening instead of preserving the pretty bits... anything less is merely the artist's ego dragging the drawing along to congratulate itself.

A drawing should only be a record of the artist's investigation of truth, and ego only obscures truth.

There you go, another life lesson from drawing.

Tuesday, March 17, 2009 at 9:40PM

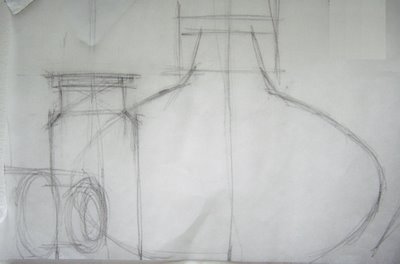

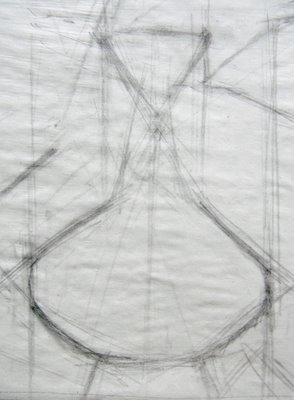

Tuesday, March 17, 2009 at 9:40PM  I'm working out a composition for a new painting on trace paper, and the new setup has several bottles and vases. I thought I'd share how I draw manufactured, symmetrical objects, since they can be tricky.

I'm working out a composition for a new painting on trace paper, and the new setup has several bottles and vases. I thought I'd share how I draw manufactured, symmetrical objects, since they can be tricky.

The least successful approach (as I have found out the hard way) is to try to draw a curvy contour and then try to match it exactly on the other side.

Instead, I start with vertical lines marking the center line, and the edges of the widest point and the edges of the width of the neck. Then I sketch a series of diamonds to mark the outermost contours. I also draw a lot of X's to see the relationships between the neck, body and shoulders of the vessel. Finally, I draw the ovals, circles, and rectangles that make up the compound shape.

Instead, I start with vertical lines marking the center line, and the edges of the widest point and the edges of the width of the neck. Then I sketch a series of diamonds to mark the outermost contours. I also draw a lot of X's to see the relationships between the neck, body and shoulders of the vessel. Finally, I draw the ovals, circles, and rectangles that make up the compound shape.

Only after that, I refine the contour. I try to be as precise as possible. Often there is a "lost edge" where the contour of the form recedes into shadow or is obscured by another shape. But I draw the entire vessel symmetrically even if part will eventually be hidden.

Only after that, I refine the contour. I try to be as precise as possible. Often there is a "lost edge" where the contour of the form recedes into shadow or is obscured by another shape. But I draw the entire vessel symmetrically even if part will eventually be hidden.

Finally I check it by looking at the drawing over my shoulder with a mirror. Errors of symmetry will jump out immediately when seen in reverse.

If the vessel in the final paintings is even slightly wobbly, crooked, leaning, or asymmetrical it will weaken the believability of the whole painting.

My new painting has two vases and three jars in the composition, and huge frothy waves of wax paper. It's my most ambitions still life yet, and the largest at 18 x 24 inches. I've spent several days sketching and re-sketching the composition on trace paper, and today I transferred the final drawing to the panel. I'll post some photos soon when I am a bit further along, but here's a sneak preview:

Wednesday, February 25, 2009 at 8:07PM

Wednesday, February 25, 2009 at 8:07PM We "warmed up" (how I loathe that word) with 1-10 minute poses, but most the session was a 3-hour pose. The drawing above is the 3-hour pose, and again I was amazed at how frantically I worked to capture the pose within the 3 hours, and felt the final drawing was not very successful.

Below was the best of the short poses from that day, a 10-minute pose. I'm not even going to post the 1-minute gestures.

When I went back to open life drawing session yesterday, I felt just these few hours of "homework" helped a lot! My gesture drawing improved greatly:

My original posts about Studio Escalier's inner movement curve concept are here and here.

Saturday, February 21, 2009 at 6:26PM

Saturday, February 21, 2009 at 6:26PM The centaur's extended leg in the lower left shows how using both approaches leads to greater accuracy. In the block-in stage the leg was elongated and stretched too far - easy to check by seeing where it falls directly under the tip of the extended elbow above. But when I corrected it I used curved method and found the correct shape according to the logic of the anatomy (which is just amazingly painted by Reni.)

I have been thinking a lot about figure drawing recently and all the approaches for teaching - not necessarily how the figure has been drawn, but how figure drawing has been taught.

The ateliers in the tradition of Gammell, Lack, and Angel all seem to use a sight-size approach and begin a student with cast drawing. I think most use the Bargue plates for beginning instruction as well. My understanding (without having studied this method) is that this trains the student to develop a highly sensitive ability to see angles, distances and values. It seems to me the goal here (again, without having direct experience) is to capture your subject exactly as it would appear if projected on the picture plane between you and the subject.

The tradition from the Golden Age of Illustration gave us constructive drawing in the vein of Bridgman and Vilppu and Reilly, (oh and Loomis), where the figure is conceived of as 3-dimensional wireframe construction of wedged rectangles and cylinders (if I may oversimplify and generalize these distinct methods). My understanding is that this is the approach used to teach animators and illustrators. The focus is on movement and the benefit is capturing gesture and pose quickly and efficiently, and teaching quickly and efficiently.

UPDATE 3/6: In the comments section of this post some excellent corrections and comments were made, be sure to read those.

Finally, as I would term it, "Expressive" figure drawing is from the tradition for teaching illustrators, but is highly influenced by expressionistic approach to fine art painting of the 20th century. The goal is to get a student to loosen up, use big arm movements, and to let go of inhibitions. I also believe this method is an ideological reaction to the art world's derision of figurative fine art in the last century, so the figure had to be approached with expressive marks to give it validity in an anti-figurative era (this is my own unsubstantiated theory). An example is here.

My teachers Ted Seth Jacobs and his students have modified their teaching from these traditions. Although Ted studied under Reilley and is connected to the 19th century academic lineage, he does not teach Bargue or sight-size. As I have documented in detail on my blog through my class notes (see "labels" in the right column), the focus is on developing an understanding of the 3 dimensional structure of organic form and the way light behaves on form. The student develops an understanding of life as organized and how each part is in harmony with the whole.

Each of these methods and their practitioners have critiques of the other methods: some lack form, some lack movement, some lack variety of markmaking, some lead to overmodeling.

I think each of these methods can benefit from the critique of the other traditions. Each approach has benefits and each has drawbacks, but ideally a student would spend at least some time studying each of the approaches.

That said... you can't go wrong by copying the Masters ;)

Thursday, February 19, 2009 at 1:42AM

Thursday, February 19, 2009 at 1:42AM This sketch took about 2 hours, and I did it entirely with the "movement curve" approach, not even a straight line block-in to start.

I notice I run into the same arc of experience when I draw: I start off, and after a good while I feel like the drawing is going well, and I allow myself to move into more details. Almost immediately I find problems, realize I need to back up to the bigger shapes and gestures... and then I spend just as much time adjusting the major landmarks as I did putting them down on the blank page!

However, once I've wrestled that together I start to understand the pose, and suddenly something shifts and all the various elements start to harmonize. It's a nice feeling.

Patience has been the key to developing my drawing ability. I would like to be able to draw more quickly at some point, though.

~~~ UPDATE ~~~

Below I've diagrammed some of the steps of my methods for how I constructed this drawing.

I started by making a mark at the top and the bottom, and would not allow my drawing to go above or below these points.

Then I drew a general gesture for the overall tilt of the main pose and a secondary line for establishing the non-weight bearing leg.

I noticed where the main weight is pressing, the ankle of the forward leg, and sketched a vertical plumb line to see what falls along that path. This is how I noticed that the raised wrist is not directly above the weight-bearing ankle, which helped me capture the general gesture. Not that I got it right at the first pass, but it helped me begin to visualize the pose on the page.

I noticed where the main weight is pressing, the ankle of the forward leg, and sketched a vertical plumb line to see what falls along that path. This is how I noticed that the raised wrist is not directly above the weight-bearing ankle, which helped me capture the general gesture. Not that I got it right at the first pass, but it helped me begin to visualize the pose on the page.

I looked for the theme (red), counter-theme (orange) and ornament (blue) to capture the gesture precisely (see my Studio Escalier notes). I spent most my time between this and the first stage, back and forth, adjusting it until it felt like the pose.

I looked for the theme (red), counter-theme (orange) and ornament (blue) to capture the gesture precisely (see my Studio Escalier notes). I spent most my time between this and the first stage, back and forth, adjusting it until it felt like the pose.

This looks wiggly and swoopy, but the lines are quite precise and intersect movement with structure. They map the paths of energy and tension that are defined by the structure of how the body is holding itself up. The axis where the curves touch the outside contour help me see the exact shape of the contour and how every part interrelates to every other part of the figure as a whole.

Once I feel I have everything working to describe the pose, I use this system to move into smaller and smaller contours of the body. Inevitably I find errors from the earlier steps - when the network of curves do not "work" within the bigger errors I have made, like the hand landing in a wrong spot on the torso would show me I've estimated the curve of the shoulder incorrectly.

Once I feel I have everything working to describe the pose, I use this system to move into smaller and smaller contours of the body. Inevitably I find errors from the earlier steps - when the network of curves do not "work" within the bigger errors I have made, like the hand landing in a wrong spot on the torso would show me I've estimated the curve of the shoulder incorrectly.

Nothing on the body has these simplified curves though - these are curves of movement, not of structure. The structure is a network of many compound curves, complexity within the harmony of the whole.

As Ted Jacobs taught me, the shapes of the body are fan-shaped and non-parallel. This translates to everything - no two high points are directly across from each other on a form. No three intersections or axis line up in a straight line.

The most difficult part was the non-weight bearing leg. That's because the limb is supporting some weight, but the upward pressure of the supported toe versus the downward pressure of gravity on the bent knee were making a curve in opposition to the general curve of gesture - two curves canceling each other out make it tempting to see a straight line, but the straight line makes the limb look rigid and dead - there must be tension and vitality, even in counter-acting curves. So I found myself struggling with it a lot, but my goal was to show the tensions without deadening the movement.

I find I also have a tendency to make everything regular and even: the first time I sketch say two curves defining the outer contours of the leg, my drawing looks awkward and clumsy and un-life like. I often wish I could see immediately what I am doing wrong, but a the stage I am at now, I can see it is wrong but not how to fix it, and I just have to fiddle around till it feels right.

I think I would be faster and more efficient if I could start to see my errors and tendencies as I make them (or even before!).

I find when drawing and painting I must suspend a certain type of evaluative, critical looking in order to work, but I need critical looking to tell if what I have drawn is satisfying, so I am always practicing and refining the skill of how to switch this critical evaluation on and off at will. So I was pleased and thrilled to find this quote by a mathematician that exactly describes this phenomenon:

"When I am working on a problem, I never think about beauty. I think only of how to solve the problem. But when I am finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong."

Tuesday, February 17, 2009 at 8:52PM

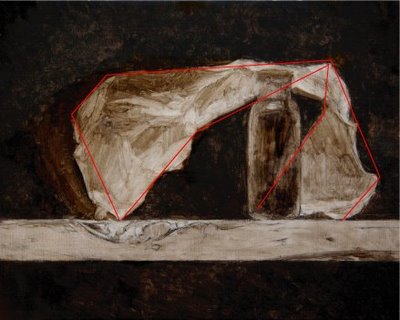

Tuesday, February 17, 2009 at 8:52PM I started with just the bottle and the shelf, I wanted to keep it really, really simple. But it just looked too boring, and after fiddling around with some twigs I finally gave in and crumpled up a small piece of wax paper and suddenly the composition was a whole lot more interesting... and also a lot harder. I was originally aiming for a 1-week painting, but this might take 2 weeks.

I thought I would share my drawing process. I diagrammed it below, on the under-painting (I did make a pencil drawing first, but I corrected the drawing with the under-painting, so I'll diagram my thinking on the better drawing.)

To start, I lay in some straight lines, trying to accurately capture the biggest, most general angles, tilts and distances. I spend quite a bit of time on this, until it "feels" like the gesture of he subject. I might break the lines into smaller segments than these, but I try not to.

Then I move into finding the curves, the major lines of movement or tension that are supporting the subject. This little piece of wax paper was behaving like an arch, so I knew I would find elements of the arch showing up here and there in the contours. The arch seems to me to have three points of contact with the board (at least from this view), so I tried to discover how it was supporting itself on these three points.

Then I move into finding the curves, the major lines of movement or tension that are supporting the subject. This little piece of wax paper was behaving like an arch, so I knew I would find elements of the arch showing up here and there in the contours. The arch seems to me to have three points of contact with the board (at least from this view), so I tried to discover how it was supporting itself on these three points.

The corners peaking at the upper right are also part of the structure, so I searched for their relationship to where the arch legs are supported.

The corners peaking at the upper right are also part of the structure, so I searched for their relationship to where the arch legs are supported.

All the folds and crumple paths along the wax paper are arranged logically for how the paper is supporting itself, or being supported. I look for the main curves of movement, and as I develop the drawing along with the panting, I'll look for the smaller and smaller incidences of how the paper is logically crumpled.

All the folds and crumple paths along the wax paper are arranged logically for how the paper is supporting itself, or being supported. I look for the main curves of movement, and as I develop the drawing along with the panting, I'll look for the smaller and smaller incidences of how the paper is logically crumpled.

When drawing the figure I follow the same method, except drawing the figure is harder.

See the first post about this painting here

Monday, December 22, 2008 at 10:56AM

Monday, December 22, 2008 at 10:56AM The format is similar to Eyewitness Guidebooks, in that the information is presented visually with lots of sidebars and with a storytelling style of writing, great for a general survey. She has included an illustrated time line for each major period of art history, which is great for visual learners.

Sister Wendy tells the history of painting in terms of the constant sweep towards and away from Classicism, the swinging between Northern and Southern European influences, and between Catholic and Protestant perspectives. After reading the book I feel like I could plot all of art history along these major axis.

As I read the book I put a sticky note on every painting I found especially interesting, and now I'm going back through all the bookmarked pages to do sketches. I've found when sketching from a heavy book, it's good to set it up in a cookbook stand. And try to keep the cat away from the piles of graphite shavings.

Sunday, November 23, 2008 at 11:27PM

Sunday, November 23, 2008 at 11:27PM So even though the composition looked nice in the sketch, the larger scale made it look overwhelming, way too big. There's a lesson in here.

It's a change for me to paint this big. The previous paintings in this "Wax Paper" series are 11 x 14 inches and 12 x 12 inches. So 16 x 20 is a HUGE leap. It may not sound much bigger, but to me it's enormous. This is the problem with blogs... there's no sense of scale.

You'll also notice the left side of the crumpled wax paper has a new shape. I decided it looked better if it angled up at the left, instead of tapering down and to a point, running off the left into infinity.... So I crumpled up the wax paper on one side (gently) and altered the composition.

I've drawn the final version on trace paper so I can transfer to the gessoed panel. I usually draw directly on the panel, but since I labored so hard to gesso them so perfectly, I was afraid of dinging or marring the perfect surface with a lot of erasing. So I nearly finalized the contour drawing on paper before transferring it.

As an final note, I'd love to draw your attention to this hi-LAR-ious blog entry by an abstract painter who says, in part:

"...what’s so hard about painting a realist painting nowadays, when even a no-talent can transfer images and paint textures straight from a computer to a canvas?"

To which I nearly choked, as you can imagine. Laurie Fendrich, I sure hope you find my link to your two posts on the superiority of abstract painting to realist painting, so you take a good look at my blog here and see that realist painting takes quite a bit of study and work, even "nowadays".

Oh, and especially note the parts about how the Old Masters used optical devices, implication being that anyone with a lens and a grid could have produced the masterworks of art history.

Le sigh....

----

Sunday, November 23, 2008 at 9:15PM

Sunday, November 23, 2008 at 9:15PM I find my paintings work best if I spend time at the beginning imagining the finished piece as clearly as possible. I try to imagine the feeling it will have. I love the feeling of calm, cool overhead light resting on eye-level objects. I want the painting to feel like you are really seeing them and feeling the quiet.

The sketch only approximates this, but it helps me crystallize the feeling in my own mind.

Saturday, October 18, 2008 at 3:53AM

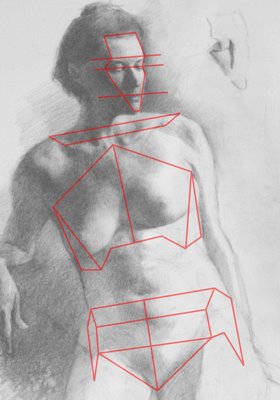

Saturday, October 18, 2008 at 3:53AM After solving the basic proportions and refining the block-in, we moved into seeing the forms as three-dimensional blocks in perspective.

To construct the major masses of the head, torso and pelvis, we identified bony projections and median lines to describe the roll, pitch, and yaw position of each shape.

I've roughly diagrammed a few of these with the red lines in the picture above. The points where lines intersect are determined by bony projections and places where the flesh attaches to the underlying bony structures. We look for indications of these on the surface of the skin, and build a concept of the box construction of each form: showing the perspective to identify tilt, position and distance.

I've roughly diagrammed a few of these with the red lines in the picture above. The points where lines intersect are determined by bony projections and places where the flesh attaches to the underlying bony structures. We look for indications of these on the surface of the skin, and build a concept of the box construction of each form: showing the perspective to identify tilt, position and distance.

Here are some of my notes from what Michael said in class:

Gesture, Proportion, Perspective

All three are inseparable, any error in one creates a series of problems in your drawing.

All the answers are within the drawing.

We need to find the points on the body that yield the most information about perspective possible. These are the distant outside bony projections.

This pattern of points starts having a profound meaning about the subject's three-dimensionality.

Let the drawing inform what your next decision will be.

Make a three dimensional drawing without relying on value - the plotting of points and median line tells you what the perspective is doing.

Look for the constructive anatomy and the perspective as a foundation for the drawing.

Anticipate without inventing: Hone the ability to see your environment through knowledge.

Drawing is like diffusing a bomb, all the concepts are a form of deconstructing and reverse-engineering.

There are two extremes, monotony versus mayhem. Our goal is to find a balance between the two.

Composition is the "composite", the entire experience of the image, from design to texture to paper to size, everything that affects the view's experience of the image.

Cut of the light - the angle of the shadow is perpendicular to the light

The image above is a detail of the small value study I did in the upper right corner of my drawing, about 3 x 6 inches. Michael encouraged us to make small tonal studies before moving forward with making a full tonal drawing. This really helped solve a lot of the major tonal decisions - otherwise it's too easy to mix light and shadow and make inadvertent holes or protrusions.

The image above is a detail of the small value study I did in the upper right corner of my drawing, about 3 x 6 inches. Michael encouraged us to make small tonal studies before moving forward with making a full tonal drawing. This really helped solve a lot of the major tonal decisions - otherwise it's too easy to mix light and shadow and make inadvertent holes or protrusions.

The lower part of my drawing shows how I blocked the terminators - delineating where the light slips over the horizon of the form. These terminators seem much softer in life, but there is a distinct moment where the shadow ends/terminates and the light begins.

The lower part of my drawing shows how I blocked the terminators - delineating where the light slips over the horizon of the form. These terminators seem much softer in life, but there is a distinct moment where the shadow ends/terminates and the light begins.

To find the terminators, which can be confusing when seeing light slide over a complicated form, Michael encourages us to find "the cut of the light" - the angle of the line perpendicular to the direction of the light source. I've diagrammed some of that here:

I also wrote down the artists and films Michael referred to in his lectures this week, here's the list and links to the best resource I could find about each (in no particular order):

Artists/Paintings/Art Movements

Brunelleschi - created/discovered our current understanding of perspective

Harold Speed

Munich School

Ashcan School

Antonio Lopez Garcia - Dream of Light

Vicent Disiderio

Neue Gallery, NY

Reubens - Rape of the Sabines

George Bellows - Use of the Golden Section

Gericault - Raft of the Medusa

Balthus

Chardin

Walter Murch

Damien Hirst

Wim Delvoye

Tim Hawkinson

Neo Rausch

Marlborough Gallery

Betty Parsons

Films

Michael references films constantly so I asked him to name some of his all-time favorite ones. This is his list, in no particular order and off the top of his head while we were talking:

The Conversation

Memento

The Lives of Others

Miller's Crossing

The French Connection

Blade Runner

Collateral

The Third Man

Kurosawa Eloru and Stray Dog

If you are interested in studying with Michael, who is a fabulous teacher, please visit Bay Area Classical Artist Atelier. He also has started his own school along with Kate Lehman and Dan Thompson: Janus Collaborative School of Art in New York.

NOTE: As Usual, My Caveat

Everything I post on my blog is my own highly subjective and filtered interpretation of my studies. My notes don't necessarily accurately reflect the teachings of my instructors, in fact my teachers may disagree or find some of my expression of their ideas to be inaccurate. The best way to understand their teaching is to buy their books and take their classes.

Tuesday, June 10, 2008 at 12:50AM

Tuesday, June 10, 2008 at 12:50AM So today I walked up the hill to good ole' Buena Vista park and did this sketch.

I'm trying not to worry too much about my paints, which are in a box somewhere in the bowels of La Poste. I'm trying not to worry that the package tracking number on La Poste's web site gives me a message that says: "Colis en instance à La Poste, destinataire avisé disposant de 15 jours pour aller le retirer." That means, "The package is at the post office, receiver (that's me) has been advised to pick it up within 15 days".

I have no idea what that means. My package is sitting in the Paris post office waiting for me to pick it up? What?? So it's looking like I might need to replace several hundred dollar's worth of good paints and brushes, but I'm holding out hope.

Yes, I have been asked by friends and family and my husband "Why didn't you insure the box?" Good question. Answers are as follows:

a) Being a tourist and a poor speaker of French I'm afraid of French government employees, including post office workers (if you have spent time in France, you are afraid of them too).

b) I don't know how to conjugate the verb "to insure" and I'm not sure they would understand me if I did.

c) I heard a rumor from another American that if your box is worth more than 100 Euros you have to fill out special customs forms and the box has to go through lots of extra vague and scary processes. So I wrote the box was worth 85 Euros.

d) I've tried to ship paint in the USA and they sure don't like it. Now I ship "vegetable oil based artist materials", but I don't know how to say that in French.

So given all that, I took a risk and just shipped the damn box, and they probably x-rayed my package and found out it's not "livres et vestements" like I wrote on the form (books and clothes, misspelled) and on the x-ray machine they saw the squiggly metal tubes and the hinges of my tiny pochade box and thought it was something they would prefer not to ship. That's my guess. But they are French, who knows. Maybe they just thought my adorable pochade box was too lovely to leave their country.

Anyway, in the meantime I am drawing in my little Louvre gift-shop sketchbook with good old pencil (did I mention my good charcoal collection is in the box, too?).

As I drew these branches I started seeing all this crazy fluid spiraling, kind of like muscles twisting around bones, with interlaced forms creating non-parallel tapering wedges .... turns out this organic, energetic human form I've been studying applies to trees, too.

Are we surprised? Non.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008 at 7:57AM

Wednesday, May 28, 2008 at 7:57AM  Friday, May 16, 2008 at 6:58PM

Friday, May 16, 2008 at 6:58PM I love this painting, how the ribcage feels like a heavy living mass of bone and connective tissues, sagging and stretching within a flexible network of skin and muscle barely holding everything together. The pelvis and ribcage are resenting their connection by the spine, each urging towards their own expression. The belly is only an afterthought, no intention of its own, merely subject to other forces. The limbs are all secondary, the gesture is complete in the torso.